National Gallery of Zimbabwe

At the very day that an exhibition with 29 contemporary artists from Zimbabwe opens at Zeitz MOCAA in Cape Town, we visit Zimbabwe’s National Gallery in Harare. Chief curator Raphael Chikukwa is not only responsible for exhibitions here, but also founding curator of the Zimbabwe Pavilion at the Venice Biennial. He explains how his success in raising international funds for the first edition in 2011, provided the leverage to convince the government to launch the pavilion. It is evident from his stories that he has been a true ambassador for Zimbabwean art. Exhibiting at the Venice Biennial pavilion has been a turning point in the careers of artists such as Portia Zvavahera and Charles Bhebe.

The National Gallery does not only engage with contemporary art but holds a collection that runs from Chris Offili back to the 17th century, stored and presented across three venues, in Harare, Bulawayo and Mutare. Significant historical donations were made by British textile magnate Stephen Courtauld (who spent the last 15 years of his life in Southern Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe), including works by Rembrandt, Caravaggio, Lucas van Leyden and many other key figures in European art history. But the majority of the collection involves art from Zimbabwe since the Gallery’s establishment in 1957. Raphael strives to make the museum as “a living organism”, rather than a depository, where curators and artists interact with the collections and bring them alive through exhibitions as well as collection mobility.

The National Gallery has two exhibitions on display, which each deserve special mention. One is the exhibition ‘The Equalities of Women’, which was assembled after an open call to women artists from Zimbabwe, South Africa and Nigeria for works addressing the position and experiences of women in society today. The exhibition includes powerful and gripping works, which touch on topics ranging from motherhood to what it means to be a woman in a male-dominated context. Over the days in Harare, this proves to be an urgent topic that comes back again and again. The open call principle is a fruitful tool to reach out to more established artists such as Portia Zvavahera, as well as less-know and younger artists, even students. Olivia Botha, for example, presents an impressive installation with textile and bloodlike liquid, in response to the illegality of abortion and its consequences for women’s lives.

Doris Kamupira shows us her installation ‘I Will Be Late for Work’. With a fashionable handbag and pair of shoes on a bedding made of sweeping brooms her work points to growing class divisions: as some women manage to enter the middle class and can afford a life with personal luxuries, the simple fact that they now do their domestic work with vacuum cleaners means that women who earn a minimal income by making simple wicker brooms are increasingly deprived of their livelihood. What if the growth of one group of women is to the detriment of others?

The participating artists we encounter at the opening, and later in Bulawayo, are very happy to be part of this all-women exhibition where they can give these topics visibility collectively.

The second exhibition, entitled ‘Meeting of Minds’ features Zimbabwean artists related to the Netherlands. Our visit was seized by both the museum directorship and the Dutch ambassador in Zimbabwe, Barbara van Hellemond, as a strategic opportunity to highlight international connection and collaboration. Having the directors of the Dutch and Danish national funds for the visual arts present at the opening of the show, sends a diplomatic message to the government that art and museums are worthy of public support.

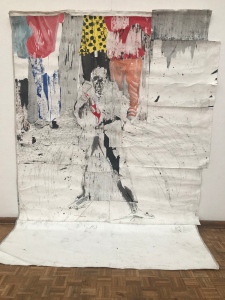

The exhibition features Zimbabwean Rijksacademie alumni Patrick Makumbe, Admire Kamudzengerere and Gareth Nyandoro (who still lives between Harare and Amsterdam), as well as artists Terrence Musekiwa and Option Nyahunzvi who participated in the Thamy Mnyele Foundation residency in Amsterdam. It is great to see their works, but also great to see Pauline Burmann’s Thamy Mnyele Foundation acclaimed for the role it plays in fostering the careers of African artists, something which is well-known on the African continent and internationally, but often remains undervalued in the Netherlands.

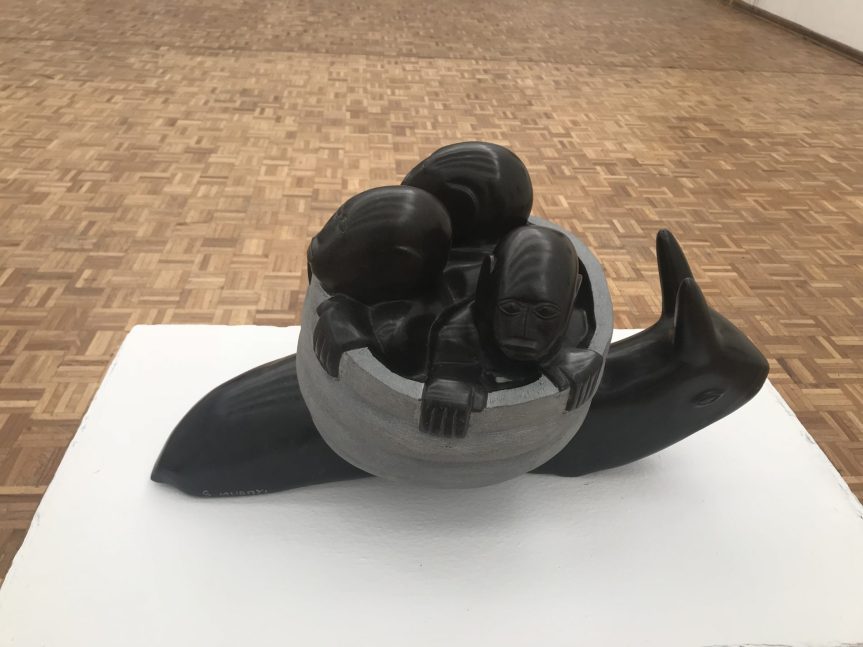

A third point of connection is Tengenenge (‘the beginning of the beginning’), an artists’ community initiated in the 1960s by Tom Blomefield, a tobacco farmer from Dutch/South-African descent, who turned his land into a sculpture farm. With the help of artist Crispen Chakanyuka, Blomefield encouraged his workers to make sculptures with the stone deposits on his land. Tengenenge continues to thrive, allowing artists with and without previous training to develop a practice and use the village as an open-air gallery and as a home for their families.

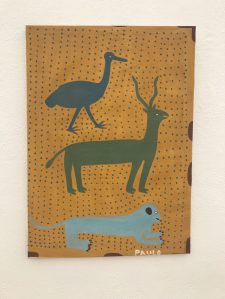

Tengenege sculptures became renowned, and the village is now hub for artists interested in stone sculpture from all over the world, as well as a popular tourist attraction. ‘Meeting of Minds’ features works by Josi Manzi, Kilala Malola, Amai Manzi, Sylvester Mubayi and Paulo Meza.

With their collection and exhibitions, the National Gallery deserves a larger audience than it is receiving now. The audience mainly exists of other artists, tourists, and school children. Others we meet in Harare confirm that music and poetry are popular art forms, but that Zimbabweans have a troubled relationship with the visual arts and museums. Raphael sketches in no uncertain words why this is the case. Historically, art museums were colonial institutions (this museum opened in 1957 as the National Gallery of Rhodesia) and a no-go area for black people. Signs on the building said: ‘no blacks, no dogs’. Museums still suffer from that colonial legacy today.

To build new audiences, and help build an art scene, education plays an important role in the museum. Not only does the museum reach out to schools, but it also provides talented youngsters with primary art education. Since there are no independent or university related official art schools in Harare, the National Gallery has taken over part of this role, with financial support from HIVOS and the Norwegian government. The entwinement of the Gallery with young talent ensures that the institution can help artists convince their families that being an artist is a respectable profession, offer them a platform with a grad show and other exhibitions, and connect them with other practitioners and professional contacts. Many go on to develop their artistic voice at Delta or Village Unhu (see elsewhere in this blog). Some also come back for further support: when Portia was selected for the Venice Biennial, for example, she was given the museum’s meeting room as a studio, so she could produce new works at a scale her own limited means at the time would not have allowed. The Gallery thus encompasses much more than what the European understanding of the term ‘museum’ would suggest and plays multiple key roles in fostering art in Harare.

Anke Bangma

Njelele Art Station

Njelele Art Station is an independent project space that focuses on contemporary, experimental and public art run by Dana Whabira and her team. The name Njelele is based on a sacred shrine in Zimbabwe and it is located in one of the oldest streets in the city of Harare. Next to engaging with local artists in the neighbour-hood, international artists can also apply for a residency.

Nancy Mteki is a Zimbabwean artist who collaborated with Njelele on her project ‘Looking for Love’. Nancy dressed herself in a wedding dress and asked a couple of men in the streets to marry her. By doing this, Nancy was reacting to the male dominance in the street in a most direct engagement. She had beautiful reactions from the people interacting with her during this project and everybody wanted to have their picture taken with Nancy.

Joyce Jenje Makwenda is an archivist-historian, researcher and author. Joyce participated in the Njelele residency exchange programme. With the help of Njelele, Joyce published various books about the influence of Township Jazz music in her hometown.

Farren van Wijk

Motor Republic Hub

Moto Republic is a space dedicated to the practice of diverse creatives that have as their shared aim, speaking truth to power. It is a cultural activist organization that promotes freedom of expression via different platforms: youth activism, music and satire, tv program’s, new media conferences, and festivals. Next to traditional funding, they finance their activities through outsourcing the expertise in house, for instance assisting in making music video clips, and hiring out their venue.

One of the platforms is Magamba TV (magamba means heroes) that provides social commentary and satire in the form of online video reports spread on social media. In a country where there is only one national TV broadcast that is connected to the state that governs all outings, Magamba TV wants to contribute to an alternative narrative. One member of Magamba TV shows us a sketch with a man seen from the back impersonating Mnangagwa (to recognize by his trademark scarf) who is in the process of selecting his ministers for the cabinet who all turn out to be friends. During the previous government one would be arrested for this kind of work, even a re-tweet could be enough.

The current government allows for more freedom, but it is still risky as the government can force social media blackouts or even arrest people at home. As a means of protection, their strategy is to put as much content online as they can, and be as public as possible, so in case things happen international media and the public are aware of it. The fact that they are ‘watched’ became overtly clear last year, when one of the buildings they are in, constructed out of sea containers, on higher order of Harare officials was tried to be demolished. Because the community demonstrated, the city managed to tear down only the 3rd layer as after the “save Moto Republic’ action they pulled back.

Bus stop TV is another, and according to our guide, most disruptive and popular (the Bus stop TV team members are “celebs”) online platform making satirical programs. Here the focus is on featuring events or topics that are taboo, through documentary stories interviewing citizens. Bus stop TV wants to create a platform for every day struggles, create a dialogue, get people’s opinion as they otherwise don’t get their voice heard.

Another initiative is Citizens Manifesto that aims for bringing citizens together and feed them with ideas how to create movements so they can have more impact. When we visit, a member of Citizens Manifesto is busy wrapping cards with USB sticks containing instructions for how to build a movement: they will be handed out for free, a physical and untraceable way of distribution.

The effect of these on- and offline activities is big: they have millions of followers both in the country but far more international. During the last elections youth contributed to the highest vote registration and also the Facebook and YouTube statistics show that there is a big group of diaspora followers.

Frederique Bergholtz