The sound of Johannesburg is different from that of Capetown.

Joburg generates the sound of a metropolis, grand and dynamic. There are also no fewer than 4.5 million people living here. That sound is not the only difference. The architecture is higher and people in the street walk differently; more self-aware. If Capetown is Europe, then Joburg is Africa. However different, both cities are marked by the history of Apartheid and the way in which history now influences the present. Also the cultural infrastructure of Joburg is different than in Capetown. It feels like the system of galleries, workshops and artists groups has become more detached from the stifling structure of Apartheid.

One of the places that undoubtedly contributed to this is the Market Photo Workshop. Founded when the Apartheid system was still very powerful: in the year 1989. The recently deceased, committed photographer and activist David Goldblatt is the founding father. Back then, MPW was an illegal organization and one of the few non-racial spaces where people could meet.

This morning Lekgetho Makola, recently the new director, receives us with his team in the gallery space of the complex. Makola says that the white Goldblatt did not just want to photograph the black youth he met in the townships. Goldblatt created for them a training facility with help of some friends. By training the youth and learning them to tell their own story with the camera, the Market Photo Workshop grew into a haven for talent development. A place where young people from the townships with their own photographs made the experiences of so-called marginalized groups imagined. An empowering force.

From the start in 1989, students themselves have found their way to the institution. Without specific PR but just because of word-of-mouth advertising. The most famous alumni of the MWP is probably Zanele Muholi who in November 2017 presented the eleventh edition of ‘Faces and Phases’ in the gallery of MPW; a series that has been running since 2006 with : “documenting black lesbian and transgender individuals from South Africa and beyond”.

Almost thirty years later, the ethos of the place remained the same: socially committed and critical. The organization has grown despite the fact that financial resources are not always easy to find. Fortunately, the institution is now partly financed with public money. Nevertheless, private funding remains crucial. There is now a phased curriculum with different programs for beginners and advanced students. Short term and long term. Attention is paid to the ethics of photography. There is a gallery and an extensive image archive. Moreover, there are international collaborations.

Makola is proud and excited. Justly. Because this morning it became known that the MPW is the winner of the annual Prince Claus Award. This means that new dreams can become reality, such as the desired international scholarship program.

As a cultural meeting place, the Market Photo Workshop has always been a non-racial space. You can still see and feel that now. Take, for example, the composition of the staff and board members present. A delicious mix of diversity when it comes to gender, age and color. The other institutes that received us were more of ‘kind of looking kind’. MPW is really different from, for example, Zeitz Mocaa with a completely black staff or the Noval Foundation with a white director and white curator. Also look at the way in which Makola replaced the chairs prior to our meeting. We are not facing each other. No, we are in a circle; staff members and we – the visitors – alternate. In this democratic setting that facilitates the conversation, stories are easily shared, questions quickly asked and answered.

The last part of this morning is filled by a meeting with photographer Dahlia Maubane who talks about her exhibition ‘Woza Sisi’; a visual study of informal economics, urban planning and employment for women – in particular women hairstylists – in Johannesburg and Maputo (Mozambique).

The title of the exhibition refers to what is called by the hairdresser to her potential client. We see how women literally claim their place in the public domain so that they can earn a little money. This exhibition also fits in with the profile of Market Photo Workshop. The gallery affiliated with the training institute shows engaged photo documentaries with social information relevant to the viewer.

Some of us want to walk on foot to next the location. But moving this way in Joburg is not recommended, again and again. As an outsider it is difficult to interpret the context properly. Are our hosts perhaps not overly worried? Yesterday I was even advised not to take 50 steps from the theater to the opposite café in a car-free street – with cheerful drinking and gender mixed people. At the same time everyone has read about the high crime rates especially the virulant violence against women. So in the end we are happy with our own mini-van with the doors neatly sealed off on the way.

Annet Zondervan

Bag Factory

The Bag Factory, located in an old bag manufacturing warehouse in Fordsburg, is the mother organisation of Greatmore Studios which we visited earlier in the week in Cape Town.

The Bag Factory is primarily a studio and residency space for artists from South Africa and broad. The building contains seventeen artists’ studios, a gallery, a lithography printing studio and project space. It was founded in 1991 by David Nthubu Koloane (°1938) and Kagiso Patrick Mautloa (°1952) as one of the first studio spaces which made it possible for black and white artists to work together on a professional level, despite the Apartheid legislation of that time. Up until today, David Koloane and Pat Mautloa continue to have their studio at the Bag Factory.

Next to studios spaces for local artists, the organisation also runs an international visiting artist programme, a curatorial training programme, as well as outreach programmes and specialized skills workshops. The international programme enables artists from Africa and other continents to spend time working in Johannesburg, creating networks, and learning about the South African culture.

The bag Factory plays an important role in Johannesburg’s artistic scene as it allows for artists, young and old, to have affordable space where they can work and meet with peers. As director Candice Allison puts it, ‘looking for space in South Africa is like looking for gold‘.

Richard ‘Specs’ Ndimande (°1994) is the youngest artist at the Bag Factory. He studied Fine Arts at the University of Johannesburg where he graduated in 2017. Richard tells us that he works in the evenings because he has a day-job as assistant in an auction house in Johannesburg. He likes spending time working in his studio at the Bag Factory because it enables him to focus on his work but also to talk to other artists and get feedback from them. For the moment he is not interested to work with a gallery. He enjoys the fact that there’s no commercial pressure at the Bag Factory even though the place is reputed to be a breeding house for artists.

Richard’s practice looks at themes of oppression. servitude and exploitation and he’s fascinated by the human-animal hybrid. Most of his works are self-portraits depicting the oppressed as prey and the oppressor as predatory beast.

Pat Mautloa is one of the founding members and oldest artists at the Bag Facorty. After working in a bank, he decided to devote all his time to his artistic work. In his work Pat uses found objects from the street in downtown Johannesburg. Gleaned objects from everyday life like wooden leftovers, worn out cotton rags or plastic jerry cans are combined with newsprints, stencils, color painting and drawing, creating abstract textures and figurative elements. As you can see here in his ‘Trump’ painting!

Finally, it’s important to mention that the Bag Factory is also very much engaged in local community life through daily care and specific outreach programmes. Candice told us that every morning they start with sweeping the whole street! By doing so they get in contact with the local people, talk about their activities and invite them to join their educational workshops, art classes and tours together with other schools and youth groups. Resident artists are also invited to participate actively in community activities and outreach programmes in the Gauteng-area as part of their residency. Thumbs up!

Lissa Kinnaer

Danger Gevaar Ingozi at Victoria Yard

Friday’s afternoon trip takes us to Victoria Yard, a newly emerging creative hub that appears hip and gentrified, yet whose social reality in the city of Johannesburg is of course only one part of a much larger, complex urban and social history and struggle for post-apartheid identity. Victoria Yard is located in Lorentzville in the east of the city center, and the creative and economic hub being put into place hosts artists, galleries, artisan and crafts makers, a brewery as well as urban agriculture and social community projects. Blessing Ngobeni, James Delanay and world-renowned photographer Roger Ballen have their studios here, and it’s scenery presents itself as a comfort zone remote to the social realities of the city.

Here we visit Danger Grevaar Ingozi (DGI), a printmaking and artist collective that moved their studio to Victoria Yards in February this year. Even though the place is “excessively romantic”, as Nathaniel Sheppard and Chad Cordeiro, the co-founders of DGI, tell us, it is attractive because of the low rents, the exposure and the overall vibrancy of the environment which aims to foster collaborative and collective practices, knowledge transfer and empowerment through an active engagement with the community. Chad and Nathaniel, who share the same passion for hip hop culture and critical discourse, took up their joint practice during their studies at the University of Witwatersrand. After leaving the safe spaces provided by the University, they decided to establish their own safe space, a printmaking studio that aspires to foster a non-elitist, collaborative approach and that provides the technical means for printmaking and its dissemination. DGI actively engages with the practices of print culture in South Africa and the socio-historical and political narratives they foster and are embedded in. The shared interest of DGI and its collaborators is the dedication to push forward print as an artistic and critical medium, as a means of knowledge production and a set of collectives practices of production, publishing and dissemination.

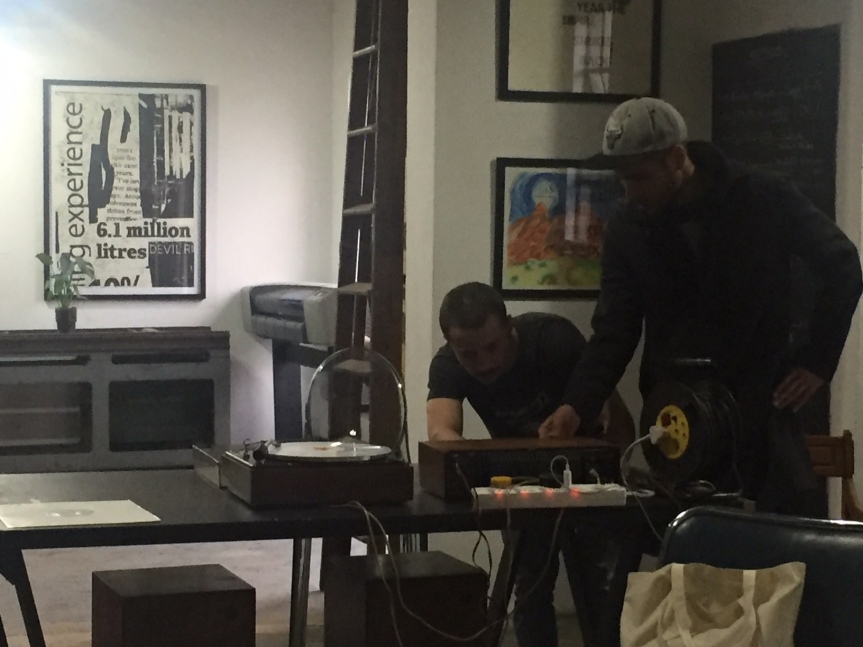

Nathaniel and Chad play for us a vinyl record that they produced within the framework of State Proof, an ongoing sonic research (and DJ) collective they form together with Johannesburg-based artist Simnikiwe Buhlungu. The project explores, through the practice of sharing, listening, conversation and exchange, private music collections and unravels the connections between the practices of music and print as sites of protest and resistance as well as the role they play as media for the production and dissemination of ideologies that can serve as counter-narratives to dominant regimes. As printing is always about questions of access and dissemination, printmaking has always played a vital role in the practice of protest. Chad tells us how in times of political upheaval and state censorship during the South African apartheid regime, printmakers would carry their silkscreens in a suitcase and disseminate among their communities important information withheld from the government. Printmaking became a powerful tool to disseminate ideologies that played a vital role in opposing the apartheid regime. The stories that DGI are invested in form part of a marginalized oral culture that still remains to find its place in the histories and heritage of South Africa.

Doris Gassert